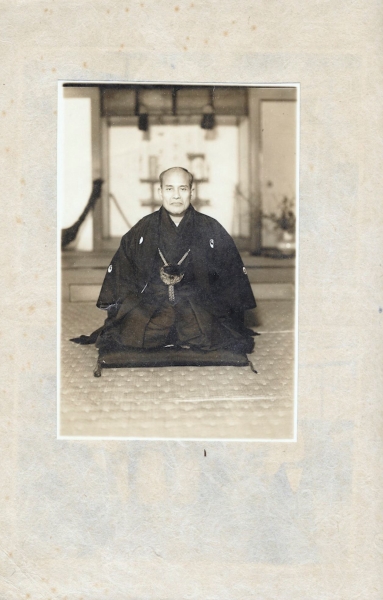

Aikido Founder Morihei (Moritaka) Ueshiba

Aikido Founder Morihei (Moritaka) Ueshiba

“Aikijujutsu Densho” AKA “Budo Renshu”, 1934

From the early 1920’s through the end of World War II Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba used the name “Moritaka” – a name he received through his relationship with Onisaburo Deguchi (出口王仁三郎), from the word “shukou” (“Moritaka” can also be read “shukou”) that appeared in Deguchi Seishi’s Norito (祝詞, “Shinto prayers”).

The actual voice of Onisaburo Deguchi chanting Shinto prayers

It was during this time period that he published the books “Budo” (1938) and “Budo Renshu” (1933), which both appeared under the name “Moritaka Ueshiba” (植芝守高).

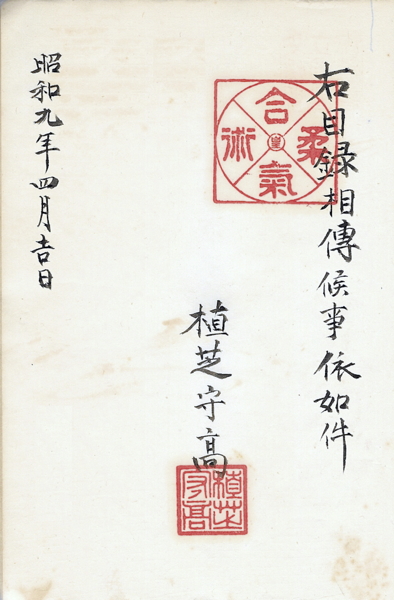

The last page of “Aikijujutsu Densho” (“Budo Renshu”) showing its

The last page of “Aikijujutsu Densho” (“Budo Renshu”) showing its

status as a licensing document, issued in Showa year 9 (1934).

Signed “Ueshiba Moritaka” and stamped (top right) “Aikijujutsu”.

“Budo” was originally created for Prince Kaya Tsunenori, a member of a collateral branch of the imperial family. Kayanomiya would eventually become Superintendant of the Army Toyama School – where Morihei Ueshiba would act as an instructor before the war. An English edition (“Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido“), translated by John Stevens, was published in 1991, and a separate edition -“Budo: Commentary on the 1938 Training Manual of Morihei Ueshiba“, translated by Sonoko Tanaka and Stanley Pranin, was published in 1999.

“Budo Renshu” (published in English under the name “Budo Training in Aikido“), published in 1933, was given to select students as a teaching license. Unlike “Budo”, which is composed of still photographs of Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating technique, “Budo Renshu” is composed of pictures hand drawn by Takako Kunigoshi, a student at Morihei Ueshiba’s Kobukan Dojo who began training shortly before her graduation from Japan Women’s Fine Arts University. This was also discussed in the article “Three Doka and the Aiki O-Kami“.

“Budo Renshu” also contains detailed written explanations of the forms and principles of Morihei Ueshiba’s art that were largely complied and edited by Kenji Tomiki, one of Morihei Ueshiba’s senior students who began training at the Kobukan Dojo in Tokyo around 1926.

More information about Tomiki Sensei is available in the articles “Kenji Tomiki: Judo Taiso – a method of training Aiki no Jutsu through Judo principles” and “Aikido Shihan Kenji Tomiki’s Goshinjutsu“.

In 1954 Morihei Ueshiba published “Aikido Maki-no-Ichi”, edited by Ni-Dai Doshu Kisshomaru (Koetsu) Ueshiba. This book, which was not publicly distributed (but is available here), duplicates most of the text and many of the drawings that first appeared in the 1933 publication “Budo Renshu”. That is to say – this book demonstrates that the technical explanations, both written and graphical, and the descriptions of principles that Morihei Ueshiba taught were the same in 1954 as they were in 1933, when the art was called “Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu”.

The document that will be available for download below, as well as the rest of the content on this site, is provided free of charge as a service to the community, and will continue to remain free of charge. You can help support this project by contributing a little bit to help support our efforts. Every donation (even $1) is greatly appreciated and helps to cover our server and bandwidth costs, and the time involved. The more support that we get the more interesting new content we can get out there!

By donating you also help support our efforts at Aikido Hawaii, which has provided a state-wide resource for all Aikido in Hawaii, regardless of style or affiliation, for almost twenty years.

Thanks,

Chris

The edition of “Budo Renshu” that will be available for download below is presented courtesy of Scott Burke, who lives in Fukuoka, but often comes to Hawaii to join the local Sangenkai workshops. He was also generous enough to provide scanned copies of “Aikido Maki-no-Ichi” and “Kenji Tomiki: Judo Taiso – a method of training Aiki no Jutsu through Judo principles“. It was issued by Morihei (Moritaka) Ueshiba in Showa year 9 – 1934.

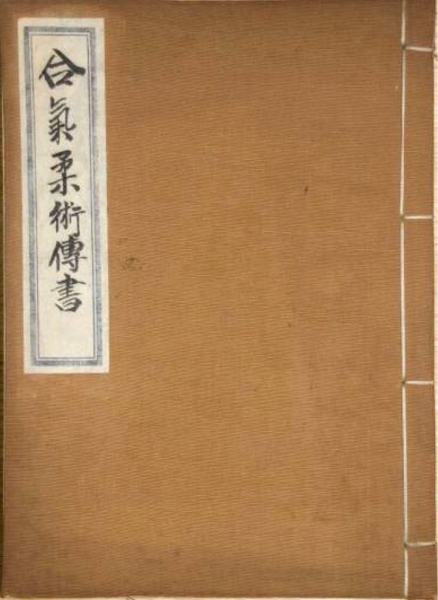

The cover of “Aikijujutsu Densho”

The cover of “Aikijujutsu Densho”

As you may have noted above, the actual title on the cover of the book is not “Budo Renshu” (武道練習), but rather “Aikijujutsu Densho” (合気柔術伝書).

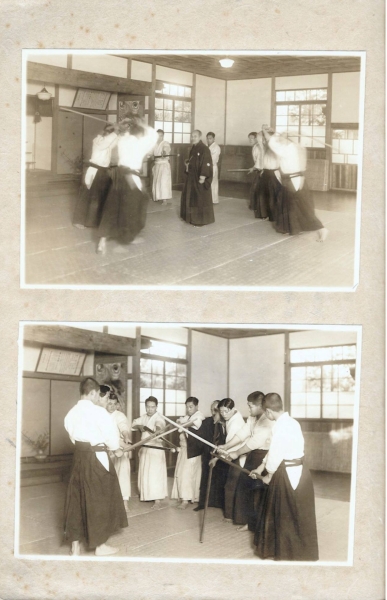

The book opens with a formal portrait of the founder (above) and includes photos of Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating Happo Bunshin (八方分身) at the Kobukan Dojo in Ushigome (Wakamatsu-vho) that opened in 1931. The technique he was showing was included in the Daito-ryu scrolls issued in that same year.

If you look closely, the person the second from the right in both photographs is none other than Aikido 9th Dan Rinjiro Shirata, who was known as the “Kobukan Prodigy”.

Happo bunshin – second from right in both photos:

Rinjiro Shirata Sensei (白田林次郎)

Shirata Sensei was one of the few post-war Aikido instructors to have received copies of both “Budo Renshu” and “Budo” directly from Morihei Ueshiba before the war.

Here’s a little interlude about Ichiro Shibata’s experiences when he encountered Rinjiro Shirata in 1977 (from “It Had To Be Felt #21: Shibata Ichiro: A Lean and Hungry Look“, by Ellis Amdur: ):

Another day that I vividly recall was during the first International Aikido Federation consolidation in, I believe, 1977. That morning, instead of Doshu, Shirata Rinjiro sensei taught class. There were easily one hundred and fifty people on the mat. Shirata sensei was allotted one and one-half hours. The majority of the students were foreign, with a particularly numerous French contingent, many of whom had high dan rankings. Shirata sensei had a very quiet demeanor, very gentle, very humble. The manners of French students were particularly appalling. Shirata sensei bowed in and started warm-ups. Many of these high-ranking Europeans started engaging in conversations, ignoring the warm-ups (these were not the dojo regulars — these were representatives of national organizations, many of whom ranked each other, who behaved with all the uncouth gaucherie of a United Nations bureaucrat with diplomatic immunity). After fifteen minutes (this was one of those “hidden in plain sight” moments — he did some solo exercises that, as poorly as I remember, I’d never seen before), Shirata sensei took a bokken. He started speaking about shihonage, underscoring what an important technique it was, and demonstrated shihogiri with the bokken. With surely a chuckle — well aware that the majority of those in the class were dismissing him merely because he was unknown to them – he said, “I’m sorry, I don’t know much about the sword. Osensei developed a lot of things after I studied with him.” The French kept talking, something that Shirata sensei ignored. I made a small mark at this point, because two of these six dans were standing, conversing in front of me, in the front row of the serried ranks of students <yes, standing!> while he was teaching, and enraged, I grabbed both of them by the koshiita of their hakama and slammed them into seiza, like cracking a whip. They whirled around and I said, “Shut the f**k up.” Cross-cultural communication — they understood my English! — and they turned around, bustling like a couple of broody hens on their knees. I suddenly felt a hard poke in my back. I turned around, ready for some kind of Gallic expostulations, and there was Waka-sensei (Moriteru), giggling with a big grin on his face.

Then Shirata sensei called Shibata-san out for ukemi. It didn’t start out well. The class was over one-half hour old, the old man had just done warm-ups and a “simple” set of sword swings, and he hadn’t exerted any authority over the class. Shibata-san, perhaps, can be forgiven, in that he reached out, in bored fashion, to take what he apparently assumed was a nice, apparently ineffectual old guy’s arm. I should mention that Shirata sensei’s hands were huge, like rhododendron bushes hanging from massive wrists. Imagine Shibata-san sticking out an arm towards the west. Shirata-sensei went further west. And further. I believe he covered one 1/3 the width of the Aikikai’s mat. Shibata-san’s face was like that of Wiley Coyote in the Roadrunner cartoons when he realizes that the rope he took hold of was attached to an anvil that had just been dropped off a cliff. The final cut of Shirata sensei’s shihonage was like Itto-ryu’s primordial cut: perfectly centered, from sky to ground, except he was cutting with a human being in his hands instead of a sword. Shibata-san made one of the most magnificent recoveries I’ve ever seen. I truly thought his arm was going to be ripped off his body, but he managed, with two huge strides and a dive to get around in time to take a thunderous breakfall. Shirata sensei threw him three more times, Shibata-san taking impeccable ukemi now, and he got up, a man in love. Others of us felt the same, both for the deserved come-uppance of our well-liked, but feared sempai, and also for this unknown-to-us, titanically powerful old man. Unbelievably, though, many of the French were still talking, casually strolling off the mat, even as Shirata sensei demonstrated another technique. Shibata-san, who, I’m sure, had been fuming at their behavior already, launched himself like an out-of-orbit comet managing a multiple attack of the entire Western world. Well, actually, he attacked the entire Western world. He was sweeping around the mat, jumping in to a pair of practicing foreigners, and grabbing one after another, launching them through the air, off the mat onto the wooden runway, or literally splattering them against the walls, then moving on to another pale-skinned pair and doing the same. It was like watching a fin-nipper in an aquarium, with all the guppies swirling away every time he drew near, one after another caught and mangled. Then, all of a sudden, he grabbed me, and spinning, wound up to throw me right into a wall. I managed to step inside him and turn, an inward tai-no-henko, spun him another half turn, and with our momentum, his back slammed against the wall. His eyes were blank and he raised a fist, but before he knocked me out, I grabbed his shoulders and yelled, “Shibata-san, Ore da! Ore da!” (It’s me! It’s me!). He shook himself like a wolf throwing off water, patted me on the shoulder and in English, said in a merry tone, “Oh, I’m sorry!” and spun away, grabbed another Frenchman and sent him flying.

The last half-hour of the class was much better behaved, I must say. Shirata sensei simply continued, unperturbed throughout the entire time, as if to say, “I’m simply here doing what I’m doing. If you want to pay attention, you are welcome.”

Just one more interesting note before we get to the download…..it is immediately apparent from comparing the post-war versions of “Budo Renshu” that were published by the Aikikai and Ni-Dai Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba (published in English under the name “Budo Training in Aikido“) to the original edition that in the post-war version many of the drawings have been re-traced. This is most-likely because they were working from photocopies or other low quality copies of the original work. What is interesting, is that many of the people in the post-war drawings appear to be….happier!

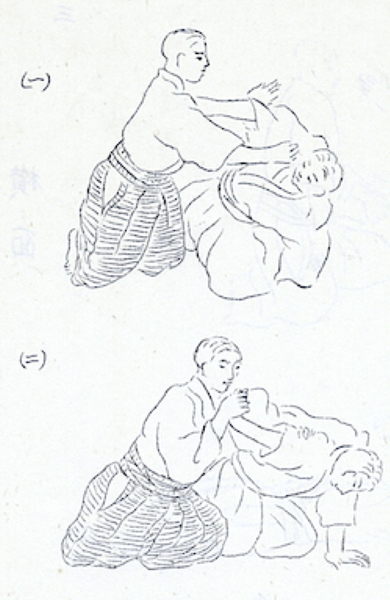

Original version – stern and focused Kobukan practitioners

Original version – stern and focused Kobukan practitioners

Note the downturned eyebrows

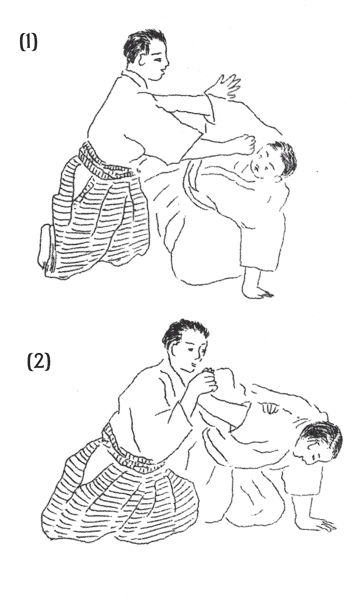

Post-war version – happy Aikikai practitioners

Post-war version – happy Aikikai practitioners

And now, the full scanned PDF version of the 1934 “Aikijujutsu Densho” AKA “Budo Renshu”:

- “Aikijujutsu Densho” AKA “Budo Renshu” (Dropbox – PDF format / 11.8 MB)

- “Aikijujutsu Densho” AKA “Budo Renshu” (Aikido Sangenkai Server – PDF format / 11.8 MB)

Enjoy!

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

Leave a Reply