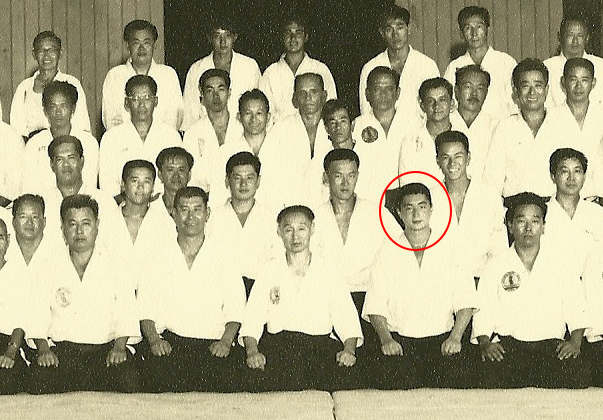

Yoshimitsu Yamada in Kauai Hawaii, 1966

What was Jigoro Kano thinking, anyway?

The other day I was reading an interview with Yoshimitsu Yamada on the Aikido Sansuikai website. This passage happened to catch my attention:

Well, the ranking system in aikido is another headache. I personally disagree with this system. A teaching certificate is okay, a black belt is okay. But after that, no numbers, no shodan, no nidan, etc. People know who is good and who is bad. The dan ranking system creates a competitive mind, because people judge others – “oh, he is sixth dan, but he is not good, this guy is much better…”

Yamada has made similar statements before, I know, but it’s always interesting when the person responsible for handing out rank to a large number of people in several countries states publicly that he is himself opposed to the ranking system.

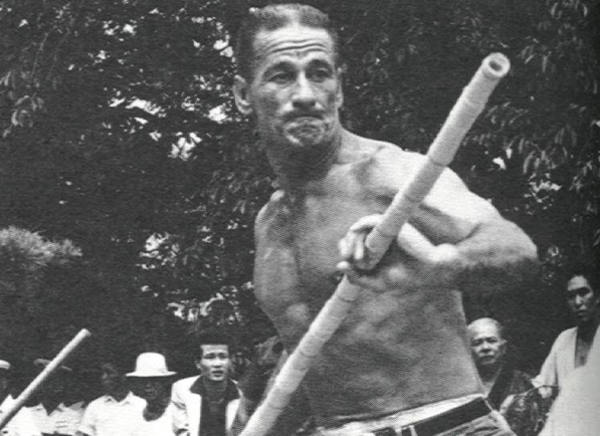

Donn Draeger – martial arts coordinator on the set of

the James Bond film You Only Live Twice (1967)

– the first non-Japanese to enter Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (天真正伝香取神道流) is the oldest organized martial tradition in Japan, dating from 1447.

You may ask how Katori Shintō-ryū is relevant to Yoshimitsu Yamada’s interview, and here it is – no ranks.

For over 400 years, there were no ranks or ranking systems, no black belts, in the traditional Japanese martial arts.

Somehow, these arts survived, and even prospered.

All that ended when Judo Founder Jigoro Kano adopted the Dan ranking system into Judo and promoted Shiro Saigo and Tsunejiro Tomita to Shodan in 1883. This ranking system would rise to great popularity in the pre-war era, eventually becoming adopted by virtually all of the modern (and many of the not-so-modern) Japanese martial arts.

Prior to that, for over 400 years, there were no ranks – no Black Belts in Japanese Budo.

Until the modern introduction of the ranking system in 1883 (and almost 60 years later than that for Aikido) people got by with a “Menkyo” certificate system that showed a persons qualification in the Ryu.

Morihei Ueshiba was a participant in such a system under Sokaku Takeda in Daito-ryu.

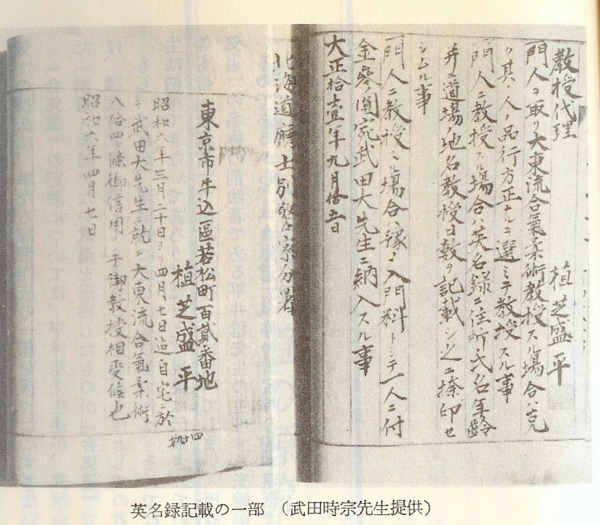

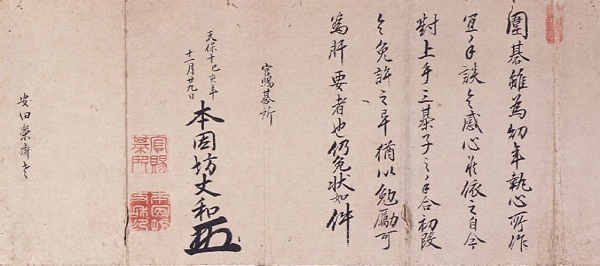

Sokaku Takeda’s Eimeiroku

Sokaku Takeda kept an “Eimeiroku” (英名録), in which each student’s study was recorded, along with a record of any licenses granted to that student.

For example, the page on the right above shows the awarding of the Kyoju Dairi (Assistant Instructor) license to Morihei Ueshiba in 1922. The page on the left is from 1931 and records that Sokaku Takeda taught Morihei Ueshiba the 84 Goshin’yo No Te techniques for 20 days at Ueshiba’s home in Ushigome (now Wakamatsu-cho).

Goshin’yo no Te (護身用の手) was the highest level scroll awarded at the time that Morihei Ueshiba was training under Sokaku Takeda.

Most of Morihei Ueshiba’s pre-war students (Minoru Mochizuki, Rinjiro Shirata, Kenji Tomiki, for example, among others) also received some version of these scrolls.

Then – the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (大日本武徳会) happened along.

The Dai Nippon Butoku Kai was organized under the authority of the Japanese Ministry of Education, and was tasked with standardizing and regulating the traditional Japanese martial arts.

The Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, for example, was responsible for the adoption of “Aikido” as the name for Morihei Ueshiba’s art.

Along with the name change came the standard Kyu-Dan ranking system established by Jigoro Kano, already in use by many other martial arts in Japan.

Both the name change and the Kyu-Dan ranking system were implemented by Morihei Ueshiba at the behest of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai in the early 1940’s.

1) This means that many of Aikido teachers instructing today are actually older than the so-called “traditional” ranking system as it is used in Aikido.

2) It also means that the “traditional” Kyu-Dan ranking system actually has no connection to traditional Japanese Budo – that it is a modern convention.

For his part, Ueshiba himself seems to have had a fairly cavalier attitude towards the modern ranking system.

For example, here’s Yamada’s opinion on what O-Sensei thought about these things:

Besides, I don’t think that O-Sensei agreed with that ranking system. To him the number doesn’t matter. Once when I was giving him a massage he said to me “Mr Yamada, what rank are you?” I answered: “I’m shodan,” and he replied: “So today I’m giving you sandan.” [laughs] Nobody believed that. I knew his personality and I didn’t take it seriously. I just answered “Thank you very much.” That is what happened.

Yamada’s not alone with this anecdote, I’ve heard the same or similar anecdotes from a number of people.

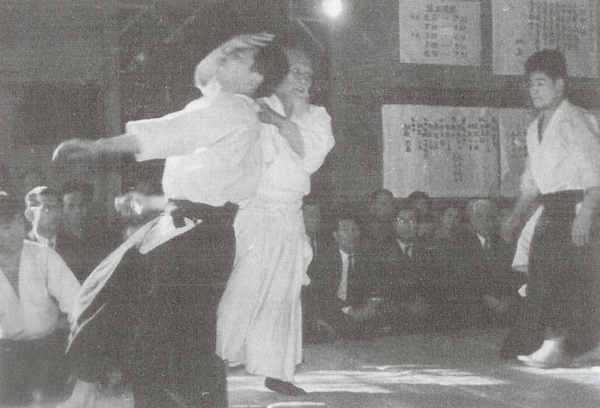

Yasuo Kobayashi (right) at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo

Another post-war student from the 1950’s, Yasuo Kobayashi, related some similar incidents that occurred around 1958:

About this time there were the following incidents. People came from the countryside suddenly demanding an Aikido 10th dan license. This was because in the old days, when O-Sensei was teaching in the local areas, he would notice someone who, for just a moment, seemed to understand, and he’d say, “Oh, this guy’s got it. I’ll give him a 10th dan.”” It seemed he would easily say things like, “You’re great! Let’s make you a 9th dan,”” to people who took him at his word, even though they may bave been only a 3rd or 4th dan. That was one face of O-Sensei. He’d just say something like, “You’re a 9th dan or 10th dan,”” When I was younger, O-Sensei told me, too, many times, that I was a 9th or 10th dan. The other uchideshi were also “promoted” to 9th or 10th dan many times.

Mitsugi Saotome, another contemporary of both Yamada and Kobayashi, related a similar story to me, in which he was spontaneously “promoted” to eighth dan by O-Sensei after having had a particular moment of insight (he didn’t actually get promoted to eighth dan until much later, long after O-Sensei had passed away).

Shusaku Honinbo’s (本因坊秀策) Shodan Certificate in Go, circa 1840

When Jigoro Kano instituted the Kyu-Dan system of ranks he adopted a system that had been in use in Japanese Go since the 1600’s, when it was introduced by Dosaku Honinbo (本因坊道策).

Jigoro Kano was an educator by trade, and was actually director of primary education for the Ministry of Education (文部省) for several years. He was also deeply committed to the modernization of Japan’s educational system, which was in the midst of a transition from the traditional system of Temple Education (Terakoya Kyoiku / 寺子屋教育) to the modern Gakusei (学制) system of education modeled on Western educational methods which was instituted starting in 1872.

Temple Education in the Edo Period

Interestingly, Morihei Ueshiba, in something of a hang-over from the Edo Period, was sent to be educated at a Shingon Buddhist temple at the age of 7.

So…why didn’t Jigoro Kano keep the traditional Menkyo system?

1) Depending upon the particular Ryu, the Menkyo system consists of any where from two to eight or so certificates, with years (sometimes many years) between certifications.

This is well suited for adults, who have long attention spans and are committed for a training span measured in years, but not so much so for children.

2) Under the traditional Menkyo systems there is no system of visibly recognizing a person’s achievements in the art – the “gold star” of the colored belt system that has been adopted into modern ranking.

Again, well suited for adults, who are (or should be) more interested in learning an art than advertising their prowess around their waist, but not so much for children.

Especially not so much for children in a modern educational system, which is built upon a structure of grades, ranks and gold stars.

And that was really the focus and goal of Jigoro Kano – to bring Judo into the modern educational system as a complementary form of physical education.

Even the “black belt”, introduced three years after the Kyu-Dan system itself, may possibly have been adopted by Kano from a school system in which advanced swimming students were divided from beginning students by black ribbons worn around their waists.

Moshe Feldenkrais demonstrates Judo with Mikonosuke Kawaishi in Paris, 1938

The system of colored junior belts (for example, white → yellow → green → blue → brown → black) wasn’t invented in Japan at all – it was introduced in Europe in 1935 by Mikonosuke Kawaishi, who was instrumental in spreading Judo to there and then later brought back to Japan. The color scheme made it easier for the students to re-dye the same belts.

Again, it was a system that was introduced for…children, and it worked well…for children.

(Note: Demetrio Cereijo notes that the colored belts may actually have been introduced in the London Budokwai by Gunji Koizumi around 1927 and later popularized by Kawaishi)

For adults and as adults, I think that most of us have some experience with the negative aspects of the ranking system. Some of us have a lot of experience with those negative aspects.

The question then becomes – what do we, as adults, get from such a system, and is it worth the price we pay?

If your answers are similar to mine, then the question may become – why don’t we just get rid of it, as Yamada himself suggested?

Of course, most organizations encourage the existence of a ranking system.

In organizational terms it makes sense – Aikido is no longer a single source art, it’s available pretty much anywhere, and if you don’t like one group then you can join another with relatively little trauma.

There’s really only one point of control these days that an organization, dojo or instructor has over their students, and that is the dispensing of rank.

Controlling who gets rank and when is the one and only control mechanism over their students outside of the will of the students themselves.

Someday it may be people will wake up to the fact that this entire mechanism is imaginary – it only works when those in the system permit themselves to buy into the premises made by the system itself.

Also making sense in organizational terms are the financial aspects.

Most large organizations (and even many small ones) survive in some large part off of the testing and promotion fees proffered by their members, which can run into the thousands of dollars for some promotions.

When Jigoro Kano introduced the modern Kyu-Dan system he also opened the door to a potentially difficult to ignore income stream for both martial arts schools and martial arts organizations.

Which brings us right back to the first question – what do we get from such a system, and is it worth the price we pay?

Personally speaking – twice I’ve made the decision to step out of the ranking system, and twice I ended up getting drawn back in, so I don’t really have any good answers.

Both times that I ended up getting drawn back in it was for the same reason – the sad fact of the matter is that most people in conventional Aikido treat you differently according to your rank. This despite the fact that most people also talk about how rank doesn’t really matter.

Because I have some particular rank people may ask my opinion about Aikido – but the guy standing next to me with a third kyu just gets ignored.

Never mind that the third kyu can kick my butt all day long – what could anyone possibly learn from a white belt?

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

I enjoyed your thoughts on this. After over 30 years of study in several different martial arts, I have formed the opinion that organizations tend to promote people who like the status provided by organizations. Unfortunately, these same people are most often not the people most capable of teaching quality martial arts. Maybe someday, organizations will develop the foresight to form a committee on “technical matters” including internal aspects, and entry into this committee will not be determined by rank… but rather anonymous vote my members. Ha ha. It might work. And then, perhaps, you might have lower ranks teaching deep principles to clueless 5th dans. Ha ha. Have a good day.

Hmm…I’ll believe it when I see it. 🙂

Best,

Chris

Hi Chris,

Thanks for this article.

Some 45 years ago I joined Judo at an university in the Netherlands.

They had a no-ranking system. From white to black by merit (through combat).

After about 6 months I was invited to join the team to a club nearby. When my

turn came I floored my opponent ( a big guy, black belt, 20+ kg more) three

times. The referee decided in favor of my opponent, imagine a white belt

beating a black belt. After the match my opponent came over to me and apologized

for the behavior of the referee.

After another 3 months I left the club, they were so in competing. After another

year I left the university with no degree for the same reason.

Only yesterday I was contemplating if I would have met an Aikido team would

that have my life ? Yes, it would greatly. I have no regrets but I will advertise

Aikido wherever I come.

Kinds regards,

Leo.

Ben, this is exactly what I have experienced as well. I have been practicing Aikido for 14 years now; 3 different styles/schools and 3 different countries. It’s the same everywhere: ranking =competition. This whole harmony/ non-competetive thing in Aikido has just developed into a ‘playing games’ sort of thing: “my toy is better than yours”. Children usually play such games in kindergarten. 😉

Absolutely I agree with the history as you have presented it, but Ueshiba’s senior students did make some use of the system to support their methodology. The first couple of Kyu ranks for Yoshinkan, Aikikai, Shodokan, and Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido are where the various systems seem to see the most obvious disparity. Yellow belts across the various systems will have different foundational material and look to be in completely divorced arts – the exercises for power and structure in Yoshinkan, the logical and methodical approach to combat arts in Shodokan, the Ki no Taiso with it’s direct connection to techniques and an opportunity to relax and explore in solo forms. Later on this becomes just different teaching methods for the same art as black belts do not look to be so different. The Kyu system reinforces How they get to minimum competence in a system.

As these things go in Japan – people follow the crowd and the dan-i system was pretty universally adopted, with each group or individual attempting to fit their methodology into that format, but the implementation of it is prone to problems. One problem is that it tends to encourage a hierarchical structure that often ends up being seniority based more than anything else. Another is that none of the major organizations that I’ve seen really have any systematic method of monitoring what’s going on – if they were universities they would be unaccredited and unaccreditable. Diploma mills, if you will.

In any case, my thinking these days is that this kind of structure causes more problems than it’s worth in the case of adult practice. People have no problems getting to a level of competence in any number of arts and sports without that kind of a system – it’s just not necessary.

One last thing to think about – Kisshomaru Ueshiba was of the opinion that it took “only two or three years” to learn the techniques (and this was pre-war he was talking about with some 3,000 techniques in the official curriculum). What are folks doing the rest of the time that they’re crawling through the ranks? Funding an organization – which he himself admitted was one of the reasons for implementing the dan-i system so strongly after the war. We need a better model for supporting organizations.

Best,

Chris

Good point. There is often time in practice minimums attached that say nothing about the ability of the student – and it should be possible for someone with related experience to advance faster. We do not have any acknowledgement of teaching ability until Fukushidoin, shidoin, and Shihan but there is no exam to verify the ability to teach or the understanding of a teaching method. Dojos have also been asked to not put many people forward for these certificates, and they do get renewed annually to make sure someone is still following the association’s dictates (and paying annual dues). I understand other groups do make this an exam.

I’ve now become a Sandan in an organization that never holds tests for ranks higher than Sandan, so I am more self-directed in my learning and I chose to look at other systems – but I have been told this may be politically ill advised. Rank becomes about politics exclusively by mid-Dan ranks that I can see.

I suppose if it was a pure meritocracy high Dan ranks would get older, and instead of more senior and more politically powerful maybe get ill, maybe become less proficient with time. We retire people in other professions.

That’s all true – but it’s not only that. There’s no process for accrediting the groups granting the ranks. I’ve been through the accrediting process for educational institutions and the standards and safeguards are very elaborate. It’s because of that process that degree granting institutions are trusted, and that the degrees have meaning. We really have nothing similar, or even close, to a process that includes peer evaluations and evaluations by an external accrediting body. That would be one option fora purpose for large organizations, if they are attempting to justify their existence.

Best,

Chris

Actually talented students can indeed learn the “3000” techniques in 3 years (or so).

However you have to understand two things:

1) when I started Aikido it was “consensus” that a Sho Dan actually indeed has to know and be able to show those 3000 techniques. In the sense of showing the basic technique, not in the sense of being able to win with it in a fight.

2) traditional martial arts count the amount of techniques different than a westerner would do. There is no “Ikkyo” and “Shi Ho Nage” (which we would count as 2 techniques), there is “Shomen Uchi – Ikkyo Omote” plus “Shomen Uchi – Ikkyo Ura” plus all the other Ikkyo you can do from other attacks. Hence Ikkyo alone is about 20 attacks multiplied by omote and ura, plus the same in Hanmi Hantachi Waza, plus Suwari Waza, plus multiple attackers, plus 3 weapons. That is easy 150 techniques: which we westerners all call: Ikkyo. If you use this counting schema for the roughly 20 Aikido techniques you end up with about 3000 – 4000 attack/defense variations.

Best Regards

Angelo

That’s a valid point about variations. On the other hand, there are quite a few techniques documented in places like the Takumakai’s Soden that are no longer practiced in modern Aikido, so I’d be hard put to say that variations are a complete answer to the count of techniques.

Best,

Chris

Ironically maybe the original intent. Grade 1, 2, 3… Yellow, Orange, Green… If training and grading was structured the same as a formal education system, then the accreditation process could be formally applied. I understand there were organizations that were taking on authority with things like Aiki-Budo was told it had to change it’s name. I can’t remember the group name. Administration rolls in a Ryu, scrolls, names of students enrolled – there seems to have been significant effort to make education verifiable for many years in Japanese arts.

The method of verification in most koryu is basically top down. That works OK with smaller groups, but not so much with the larege, diffuse groups in modern martial arts. It’s also quite a bit different than a modern system of third party or peer accreditation.

The Dai Nippon Butokukai made some efforts to standardize Budo before the war, but that wasn’t part of its original charter, that occurred as part of the pre-war Japanese militarization of Budo in order to promote the war effort.

Best,

Chris

Chris, as I heard it from a couple of experts in Chinese martial-arts, there used to be an old saying in China about Shuai Jiao (the precursor art to Judo, Ju-jutsu, Sumo, and others) to the effect that you should be careful about challenging someone with a black belt (it was an obi, just like the ones the Japanese adopted). It was traditional to not wash the obi, so with a lot of practice the obi would turn black. Hence a “black belt” represents someone with probable skills developed in a lot of practice.

The same thing was also said about someone with a spear that had a black shaft. After a lot of usage, the white-waxwood shaft would be black from handling, so the idea was to be careful challenging someone with a blackened spear shaft.

Thanks Mike!

Best,

Chris

Our organizations are led based upon individuals’ ranks; we convince ourselves that those ranks are issued based upon objective ability and that we strive within meritocracies, when in fact there is no objective way to measure Aikido skill and knowledge and we find ourselves instead in gerontocracies (rule by age/seniority). Testing for rank supposedly requires demonstration of higher skill levels, but the actual test requirements in pretty much every organization are based upon technique, not skills (food for a separate discussion); in what way is “shodan level” shomenuchi ikkyo *measurably* different than 6th kyu level shomenuchi ikkyo?

I had an intriguing conversation many years ago with a young bagua-zhang instructor who insisted that all martial arts across the globe have been affected by the kyu/dan ranking system; as a result, all martial artists have become trapped in an enforced parent/child relationship with their teachers that lasts their entire adult lives which becomes increasingly harmful for everybody the longer it lasts. The junior is held in the role of submissive receiver, and the senior is held in the role of infallible teacher when after decades the difference in their time-in-training becomes increasingly meaningless – when historically, every martial art had to be transmittable in a handful of years or the students wouldn’t live long enough for the art to matter. It was an interesting premise!

I have recently also spent a lot of time thinking about western academic models – bachelors, masters, PhD degrees being roughly analogous to the menkyo systems. In academia there are also “professional” ranks – asst. professor, full professor etc., and now increasingly there are specialty certifications being issued by many institutions. However, regardless of one’s degree institution or how long one has held his or her degree (1 year or 40 years), PhDs are respected as peers. There’s an old joke in academia – what do you call an individual who barely graduated last in his class with a PhD from Podunk College, Alabama? Doctor. What do you call an individual who graduated Magna Cum Laude from Harvard Medical School? Doctor. Further prestige and status among academics has to be earned by performance. Also worth thinking about.

At any rate, I just wanted to comment that this is a well-researched and valuable article, thanks for taking the time to put it out there.

Thanks Guy, and thanks for the input!

Best,

Chris

Koryu has a very different mandate than a modern budo, particularly those modern schools embracing a competitive element, hence teaching ability is favored over technical ability. For this reason, not only do we not issue ranks in TSYR, they are specifically prohibited in our kaiki. As historical preservationist, the key to a koryu’s survival is cultivating teaching skills. A really detrimental side effect of a technical ranking system is the automatic assumption that technical skills infer teaching skills. In my experience, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Regards,

Tobin Threadgill

Absolutely! The best performers rarely make the best coaches, and vice versa. That doesn’t even get into administrative and organizational skills, which are also often decided by rank or seniority.

Best,

Chris

The kyu-dan system has been adopted by professor Kano when his organization started to grow. As in Judo there is randori, it was felt important to know immediately what level a visitor was, so as to be able to use the right amount of force. White: he is still learning ukemi. Brown: he can fight but he is not very experienced. Black: we can test him with all our force.

After, the black belt magic impressed the mind of the common people

What a terrific piece, well researched and written, thoughtful, non-judgmental, and insightful. I loved it. I’d like to quote from it in one of my next books. Any objections?

Dan

Sure Dan, I’m glad you liked it! Great to hear from you again.

Best,

Chris

Very interesting post, rank is something very subjective not only within Aikido but also compared to other martial arts. People should be realistic and honest with themselves about the rank they have achieved, because the governing bodies of the organizations will not so easily do away with ranks, be it for better organization or profit. So it’s up to the individual to value and represent his rank accordingly, and recognize what merits earned him/her that rank, be it technical skill, support to their community and Dojo, time and dedication to their practice, etc.

Thanks for the article, I enjoyed reading it a lot.

The further we go loosing the cultural roots of our art in Japan we’re at loss how to replace it. To late to return to an older system that most of us have no connection with, and no guidance of what to replace our present system with. It comes down to what the individual Western teacher feels like doing.

My teacher always viewed the grading system as simply an affirmation of your level of skill, and not as a means to an end. Only awarded once earned. Never asked for nor trained exclusively for. I try to stick to this criteria but yes it’s not always easy. We don’t have coloured belts, not even for the kids. Only white and black. I like the idea that a Shodan needs to be able to instruct what he knows, clearly with understanding. This may take a very long time to achieve. Some never getting there. Yet I do figure in time spent and personal consideration. It’s not all the same across the board. People are different.

But hey I’m happy to give up the blind adherence to formal organisational structure paying enormous amounts of money for a nice certificate that I can’t even read.

But first most I better get my own shit in order. Since meeting Dan Harden I consider myself hopelessly inadequate to be an authority in my own Martial Art. Things may change.

Great post, just a few points:

1. It’s been definitively proven that Kawaishi sensei did not invent colored ranks. They were definitely in use at the Budokwai in London before he arrived there. They were even in use at the Kodokan prior.

2. Recent research shows that it was Prof Kano who introduced Dan ranks to swimming, not the other way around.

Please see my post: https://martialhistoryteam.blogspot.com/2020/05/martial-arts-ranks-clarifying-origins.html

Thanks Richard!

Best,

Chris