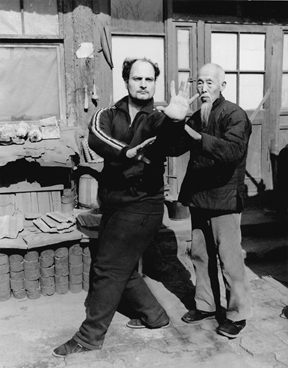

Bruce Frantzis and Liu Hung Chieh, a master of Bagua, Tai Chi, Hsing-i and Taoist meditation

静中触动动犹静

“Seek motion in stillness, seek stillness in motion.”

The Taiji Classic – “Song of the 13 Postures”

動中静、静中動

“Stillness in motion, motion in stillness.”

Seigo Yamaguchi Shihan, Aikido 9th Dan

静中の動。合気道の基本は此処に存するといわれている。

“Motion in stillness. It is said that here is the foundation of Aikido.”

Ni-Dai Aikido Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba

静動一致

“The unity of calm and action.”

(Official English translation – the Kanji read “stillness” and “motion”)

Ki-Society Founder Koichi Tohei

Some more thoughts about Aikido’s Chinese heritage

Bruce Frantzis spent some sixteen years training in China, Japan and India in Tai Chi, Bagua, Hsing-I, Qigong, Yoga and Taoist meditation. From 1967 to 1969 he also trained at Aikikai Hombu Dojo, and was able to attend classes taught by Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba. He is the author of a number of books, primarily relating to Chinese Taoist meditational methods and Chinese internal martial arts.

In an article on the Energy Arts website he speaks a little bit about his experiences with O-Sensei, and about his theories about the sources behind O-Sensei’s unusual strength.

“I studied with O-Sensei Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido, during my undergraduate days in Japan. My research has indicated that O-Sensei’s aikido was in a primary way directly influenced by bagua zhang. My first in-depth, extended experience with a top-level master of internal martial arts was with Ueshiba between 1967 and 1969.”

It’s quite interesting that Frantzis unequivocally places Morihei Ueshiba in the same category as the Chinese internal martial arts instructors that he trained under.

He’s not alone – in the diagram in this article Keisetsu Yoshimaru directly equates the Kokyu Ryoku (呼吸力 / “breath power”) used in Daito-ryu with the explosive power expressed in the Chinese internal martial arts.

However, that very assertion by Yoshimaru (a Daito-ryu practitioner), which shows internal power coming directly to Daito-ryu from Sokaku Takeda without a detour through O-Sensei, shows the difficulty in arguing that the source for O-Sensei’s unusual power was direct instruction in a Chinese internal martial art.

It becomes even more difficult when considering that there were a number of people in Daito-ryu, such as Kodo Horikawa and Yukiyoshi Sagawa, who had no real connection to O-Sensei but were able to duplicate his feats of martial prowess.

The common thread, of course, being Sokaku Takeda.

(On a related note, you may be interested in this very interesting study by John Driscoll, originally published on AikiWeb, that shows the almost exact correlation between the techniques taught by Morihei Ueshiba and the techniques of the Daito-ryu Hiden Mokuroku.)

I’d go further to debunk the notion of Morihei Ueshiba as a direct student of the Chinese internal martial arts, but it’s already been done – Ellis Amdur covers this topic in some detail in “Hidden in Plain Sight“. If you haven’t read it yet then I suggest you make it your next stop for more information about Chinese influences on Japanese martial arts and internal martial arts training in Japanese martial traditions.

Stan Pranin also addressed this issue in a recent article on the Aikido Journal website, in which he shows that the argument made by Bruce Frantzis is not historically demonstrable based on what is now known about Morihei Ueshiba’s life.

All of which I agree with.

But there is a separate discussion here, the issue of a historical Chinese influence on Japanese martial arts in general, and on the arts that Morihei Ueshiba studied in particular, that is not addressed in Stan’s article.

In this respect the sub-title of Stan’s article (“Proponents of the theory of Aikido’s Chinese origin must provide proof.”) is somewhat misleading.

Japanese “Kentoshi” (遣唐使 / “envoy”) ship to Tang China, circa 630 A.D.

Was there a Chinese influence on Morihei Ueshiba?

In a general sense, yes, there can be absolutely no question. Chinese influence on Japan and Japanese culture was pervasive and continuous throughout Japan’s history, and there was continuous interchange between the cultures for more than a thousand years. Everybody knows this.

When Morihei Ueshiba wrote a sentence he wrote it in Chinese characters.

When he was a child he was educated through the memorization and repetition of Chinese classical texts.

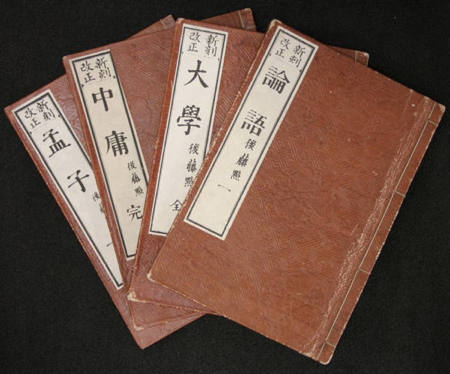

Shishogokyou (四書五経 / the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism)

This was normal at the time – Hiroshi Tada was educated in the same manner, even though he was a generation younger than Morihei Ueshiba:

“From childhood one would recite the Shishogokyou (四書五経 / the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism) and execute that mindset. I was raised in that world, but now it is completely different.”

You may also remember this interview, in which Hiroshi Tada stated his opinion that “the most influential person in the history of Japan” was Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師), who founded Shingon Buddhism by importing esoteric Buddhist teachings from…China (do I need to mention here that Morihei Ueshiba was educated in a Shingon Buddhist temple?).

Further, when Morihei Ueshiba expressed himself he often used obscure Shinto terminology from the Kojiki (古事記). The Kojiki was the first recorded instance of writing in Japan – compiled around 712 A.D., it was written phonetically in Chinese characters.

Many of the tales from the Kojiki are repeated in the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), published just eight years later in 720 A.D.. The Nihon Shoki was written in classical Chinese, includes many quotes from Chinese classics and chronicles and was modeled after Chinese classical annals.

單刀法選 – Dan Dao Fa Xuan – Chinese Long Saber

The two way cultural influences are well documented, showing the existence of communication and interchange between the two cultures.

For example, 400 years ago, in ancient China during the Ming Dynasty, there were constant battles with the Japanese pirates. 單刀法選 (Dan Dao Fa Xuan) is an ancient Chinese sword manual that documented the swordsmanship from these battles. Cheng Zong You, the author of the manual, trained under Liu Yun Feng, who learned Japanese Kenjutsu directly from the Japanese.

Then, going back to Japan, we have the Japanese word “Sumo” (相撲), which uses the Chinese word “Xiang Pu” (相扑), meaning “wrestling”.

The Japanese national sport of Sumo (which both Sokaku Takeda and Morihei Ueshiba practiced) was imported from Tang Dynasty China, complete with the identical organizational structure and rituals employed by the Chinese.

Of course, all of this is not surprising when you realize that the distance between China and Japan is only slightly more than the distance between Paris and London.

So, everyone who’s seen chopsticks can see the clear influences on Japan from Chinese culture. Does that mean anything?

Even assuming that Morihei Ueshiba, like everything else in Japan, was influenced by Chinese culture, was there a specific influence on Aikido as a martial art, and is that important?

Kiichi Hōgen and Oumaya Kisanda, woodblock print from 1829

Well, one of the strongest arguments in support of the existence of such an influence, and its importance, is that Morihei Ueshiba said himself, repeatedly, that there was a specific Chinese influence on Aikido as a martial art, and that it was important.

Remember “Kiichi Hogen and the Secret of Aikido“? In that article we saw how O-Sensei stated clearly, to a number of his students, that the secret of Aikido was to be found in a Chinese text of strategy.

Remember “Aikido and the Floating Bridge of Heaven“? In that article Morihei Ueshiba describes Aikido in the terminology of the classical Chinese martial arts.

And how about “Aiki, Iki, Kokyu, Heng-Ha and Aun“? Which further explicates the Founder’s used of Chinese terminology to describe Aikido, and introduces the basic eight power structure from Chinese internal martial arts that we talked about in “Aikido without Peace or Harmony“.

Does it matter?

Let’s assume for the moment that Morihei Ueshiba modeled his methods and terminology after Chinese martial traditions. Why should it matter to you?

Well, it’s no news to anybody that the writings left behind by Morihei Ueshiba are very difficult to understand. In “Morihei Ueshiba: Untranslatable Words” we saw that even Nobuyoshi Tamura was known to tear his hair out over the Founder’s terminology.

Frankly, it’s very difficult to understand anybody about anything, even in English, without some knowledge of the context in which they are speaking. The more difficult the subject the more important it is to understand that context. This is especially true in Japanese, which is a highly contextual language composed of multiple homonyms – many of which are employed to add additional layers of meaning that may not be apparent in translation.

Morihei Ueshiba made heavy use of Shinto terminology – but it is clear, to me at least, that this terminology is used to express concepts from th Chinese internal martial arts, and that this is the context in which he is speaking much of the time.

I think that if you read Morihei Ueshiba in the original Japanese you will find that double (and even triple, at times) encoding of layers of meaning was quite common for him, but I think that you will also find that reading the texts in the context in which he was speaking will make them understandable in a way that they were not previously.

And it seems to me that anybody who is interested in Aikido really ought to be interested in what Morihei Ueshiba had to say about the art. It’s a no-brainer.

When you don’t understand what O-Sensei had to say (and it is well documented that one after another of his direct students stated that they were unable to understand him) you sever the Kuden (口伝), the oral transmission, from the art of the Founder. And in traditional martial arts, in China or Japan, it is commonly the Kuden that provides the keys to unlock the training that is being transmitted.

Stan Pranin addressed the question of whether or not Aikido as we know it today is really the creation of Morihei Ueshiba in his article “Is O-Sensei Really the Father of Modern Aikido?“. In this article the basic approach to the argument is to examine the number of contact hours that each student actually experienced, but he also notes (referring to Morihei Ueshiba):

“Even when he appeared on the mat, often he would spend most of the hour lecturing on esoteric subjects completely beyond the comprehension of the students present. “

Students of the Founder who missed a lot – who got what they got by feel, through being thrown directly by the Founder, but were missing the keys to unlock what they received, because they could not understand the Kuden that were being given them by the Founder. Yasuo Kobayashi, who was one of those students being referred to in the quote above, put it this way:

“O-Sensei would only show technique, with barely any explanation. He would often speak of the Kojiki or Omoto-kyo, but unfortunately for me understanding the content was like trying to grab clouds. At the time all I could think was ‘When is he going to start moving?’ (laughs). When I recall it now I wish that I had listened more at the time.”

A corollary to this theme is that those students who got a lot of “something” from the Founder then had problems transmitting that “something” in turn to their students, because they lacked the language and concepts to explain what they had received from the Founder through direct experience.

How many of us have become comfortable with not really knowing or understanding what the Founder was talking about?

Ask most senior Aikido instructors for clear explanation of the terms and goals expressed in “Takemusu Aiki” and you’ll get…very little. It is incredible, to me, that an instructor in an art is comfortable with not understanding with any clarity the speech of the Founder of their art.

It’s easy to see how this leads to a breakdown in the transmission, a steady degradation of skills where the students of the Founder never quite match the level of the Founder, the students of the students never reach the level of their teachers and so on. Now that we are, in many cases, four and five generations away from Morihei Ueshiba the trends are clear to those who will take the time to see.

We can only hope that it is not (quite) too late, to turn things back.

Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

All of the content on this site is, and will continue to be, provided free of charge as a service to the community. You can help support this project by contributing a little bit to help support our efforts. Every donation (even $1) is greatly appreciated and helps to cover our server and bandwidth costs, and the time involved. The more support that we get the more interesting new content we can get out there!

By donating you also help support our efforts at Aikido Hawaii, which has provided a state-wide resource for all Aikido in Hawaii, regardless of style or affiliation, for almost twenty years.

Thank you for your support and encouragement,

Chris

![Cuatro Generaciones de la Familia Ueshiba [Spanish Version] Mitsuteru Ueshiba Sensei in Hawaii](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/chris-li-mitsuteru-ueshiba-2010-1-150x113.jpg)

Fantastic article.

Thanks John!

Best,

Chris

Hello Chris.

I enjoyed your sentiments, as I share them. It is my opinions that the some of the classics on internal martial arts can be very informative in researching Aikido (the practice). Perhaps due to translation, and certainly due to the intellectual approach by some modern translators, much of O’Sensei’s writings are not often as useful as some of the Chinese writings on martial arts (especially the work of Sun lu Tang and Professor Cheng and even translations on Taoist Alchemy by Cleary). Aikido, as commonly taught, has some weak points in its foundation. If a building is to reach any height, its foundation must be strong. May the current and future generations lift this art to its potential!

Ben

Hi Ben,

O-Sensei can be startlingly clear, the primary challenge is to get what he was saying into the proper context. Not always so easy, unfortunately… 🙂

Best,

Chris

I agree with your comment on the importance of context and how “startling” clear the man could be. I find it to be so as well. Thanks for all your work.

Ben

Thanks for all your work.

Greetings from Chile

Thanks Sergio, I’m glad that you’re enjoying it.

Aloha from Hawaii!

Best,

Chris

So your conclusion is that although O’Sensei developed the same Ki skill as Chinese Internal Arts masters, he arrived at it independently? Quite believable. As a long-time Aikido student of Saotome Mitsugi Shihan and Ikeda Hiroshi Shihan, I’ve relocated to Taiwan where I’ve been engaged in the study of Chinese NeiJia as well as continuing Aikido for the last 5 years. My purpose is to infuse or inform my Aikido with these internal martial arts principles and maybe (although I’m afraid my age does not allow sufficient time) become proficient at the three forms of NeiJia as well. One interesting aspect I find in comparing both arts is the clear delineation between cultivation and application in the Chinese Arts. Various practices are explained specifically for cultivation of Ki and the ability to extend it. I’ve never seen that line drawn in Aikido – application and cultivation seem to be taught simultaneously from the inside out or the outside in, depending on your teacher’s perspective. Unfortunately Mr. Amdur’s book is not available as a Kindle edition but as soon as it is, I intend to read it. Can you direct me to any other sources of these “lost practices” of cultivation in Aikido?

No, I would say that the Chinese influence is very clear, but that he got it from Sokaku Takeda. Ellis’ book is a must read, since he closely traces the influence of Chinese internal arts on Japan. Other than that, there’s a lot of information out there, but it’s mostly scattered, or in the hands of people who are teaching this kind of thing – like Dan Harden.

Best,

Chris